|

|

|

The Big L Tapes The Tony Blackburn Show

The Keith Skues Show

The Penultimate Fab Forty

The Final Fab Forty

The Mark Roman Show

The Ed Stewart Show

The Chuck Blair Show

The Perfumed Garden

The Chuck Blair Breakfast Show

The Pete Drummond Show

The Last Three Hours

Big L extras

Radio Caroline

|

Background Notes The pirate stations - a brief introduction COMMERCIAL TELEVISION - in the shape of the regional ITV stations - came to Britain in the mid 1950s, but nothing was done about radio, where the BBC still had a monopoly. (Radio Luxembourg broadcast programmes in English in the evenings but, despite its powerful medium wave transmitter, reception quality in the UK was often poor.) In March 1964 the first British 'pop pirate' - Radio Caroline - began broadcasting from a ship anchored off Felixstowe, just beyond the UK's three-mile territorial waters and thus outside British law. Radio London followed in December, and over the next couple of years a dozen or so other stations began broadcasting from ships and former wartime forts. For British listeners, the pirates were a revelation. They played pop records all day, together with advertisements and jingles, all presented in a chatty style by friendly disc jockeys. They were very much in tune with the explosion of fresh ideas and different lifestyles which characterised the 1960s, and with the rise of British pop groups such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. The contrast with the BBC was huge. The Corporation played very few records and its style of presentation was very old-fashioned: programmes were entirely scripted and announcers were not allowed to ad-lib.

Radio London  photo: Wikipedia Radio London - 'Big L' - was the most successful of the pop pirates. It began broadcasting on 23 December 1964 from a former US minesweeper. Its programming was based on the 'top forty format' used by American stations. Over the following three years it achieved an audience of 16 million and its disc jockeys - including Tony Blackburn, Tony Windsor, Kenny Everett and Dave Cash - became household names. It was the first pirate to broadcast news bulletins and the only one to make a profit. Harold Wilson's Labour government did not approve and claimed that the pirates were dangerous because they interfered with ship and aircraft communications (no evidence for this claim was ever produced) and that they did not pay performing rights fees (this was also untrue). The government therefore tabled a bill to make it illegal for British citizens to work for or cooperate with the pirates, and this became the Marine, &c., Broadcasting (Offences) Act 1967. When it came into force, all the pirates except Radio Caroline closed down. Big L ceased broadcasting at 1500 on Monday 14 August 1967. It is difficult now to appreciate how sad an occasion this was for the millions of people for whom the station's disc jockeys had become constant companions. If you're interested in exploring the subject further, Google 'pirate radio stations 1960s' and you'll find that there's a huge amount about them on the internet, including the excellent Pirate Radio Hall of Fame. There's also a lot on YouTube: try this film about Big L for example. But, above all, you must visit the Radio London website, run by Chris and Mary Payne. This amazing site has thousands of pages with an extraordinary amount of information, including every 'Fab 40' broadcast by the station. (The site also contains information about Radio Caroline and some of the other pirate stations.) Incidentally, Mary Payne has been a lifelong devotee of Radio London. You can hear her mentioned in the final Chuck Blair show (14 August 1967) at about 0822 (at 2:45:51 in the audio file). He is reading out some dedications, one of which concerned Mary who had 'sent lots of articles and done a lot for Big L'. That was Mary Payne. And, last but not least, try RadioFab where you can buy, among many other things, The Wonderful Radio London Story - the book by Chris Elliott (£24.99) and the 3-CD set narrated by Keith Skues (£29.99) - both are excellent.

1967: Making the recordings

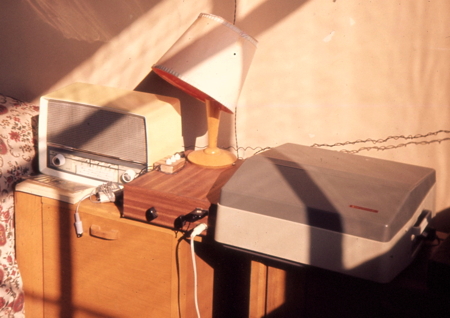

based on Google maps Tapes 1-3: Radio London I was a loyal listener to Radio London from its very early days. I was at Westminster (teaching training) College in Oxford at the time, and I can remember sitting with friends on the sports field just behind the student houses on summer Sunday afternoons, listening to the Fab 40 on a portable radio. In 1967, when I heard that the station was to close, I decided to record a few programmes before it was too late. The recordings were made at the family home in High View Road on the western edge of Guildford in Surrey. High View Road is on the north side of the Hog's Back just off the A31 and, as its name implies, is on relatively high ground (about 108m above sea level). It was therefore in a reasonably good position for receiving the signal from Radio London's 50kw transmitter on 266m in the medium wave band. The distance between the house and the Radio London ship, anchored 5.6km (3.5 miles) off Frinton in Essex, was about 145km (90 miles): reception quality was good during the day but variable at night. (The ship's exact position was 51 degrees 47.9 minutes N; 01 degree 20.55 minutes E.) I used ordinary domestic equipment to make the recordings: an Ekco medium-wave and long-wave (AM) mains radio was connected to a Philips open-reel tape recorder. They are seen here in my study at Westminster, the radio on the left, the tape recorder on the right (with a gadget in between whose purpose I've forgotten - I think it was a home-made amplifier).  The tape recorder could record in stereo (two tracks each way on a tape) but since the broadcasts were in mono, I recorded them in mono, which meant I got four separate tracks on each tape. The tape recorder accepted 7 inch tape spools, allowing for just over 90 minutes continuous recording at 3¾ inches per second (ips) or a little more than 3 hours at 1 7/8 ips with a slightly poorer recording quality. I recorded Big L's last three hours at 3¾ ips (which meant turning the tape over half way through); all the rest were recorded at 1 7/8 ips so as to get complete three-hour programmes on a tape. Tape 4: Radio Caroline Caroline continued broadcasting despite the Marine Offences Act by servicing its two ships (north and south) from the Netherlands. The south station broadcast on 259m medium wave from the Mi Amigo anchored four miles off Frinton. In February 1968, six months after the other pirates had closed, I recorded some programmes from Radio Caroline. Sadly this tape was later used (by someone else!) to record a BBC programme about Beethoven. As a result, about half the Caroline recordings were erased. What's left is the last 18 minutes of a Stevie Merrick Show, and a US Hot 100 Show presented by Roger 'Twiggy' Day, followed by the start of another Stevie Merrick Show presented by Andy Archer. Incidentally, Radio Caroline is still broadcasting - now on the internet. You'll find it here.

2020: Digitising the recordings  I found the tapes (branded 'Tudor Tape' - fairly cheap if I remember rightly) amongst a lot of junk when I was clearing out cupboards during the coronavirus lockdown in April 2020. I wasn't sure they would still play - they were 53 years old - but they did. In the mid 1970s I'd replaced the old Philips tape recorder with an Akai stereo tape deck model number 4000DS Mk II (pictured). Fortunately, I still have it and it still works well. I connected it to the audio-in socket on my (2011) iMac and used SoundStudio to record the tapes as digital audio files. The Akai has two tape speeds - 3¾ ips and 7½ ips - but not 1 7/8 ips. However, digital audio technology made it possible to restore the recordings: I played the tapes at 3¾ ips and then digitally halved the speed of those which had been recorded at 1 7/8 ips. I checked the pitch of some of the records played in the programmes against CD versions of the same tracks and, where necessary, increased the pitch of the recordings by a semitone. I then applied a 10-band graphic equalizer to increase the treble and reduce the bass frequencies. This was especially effective in the case of the tapes recorded at 1 7/8 ips. Finally, I created mp4 files of the programmes with a bit rate of 128kbps - more than adequate bearing in mind the quality of the original recordings. Each link in the left-hand column at the top of this page will take you to a page where you'll find notes on the recording and an analysis of the programme (listing the records and advertisements played) and from where you can listen to the audio file. I hope you will enjoy listening to these historic recordings and that, if you're as old as I am, they will bring back happy memories for you. If you have any comments or questions about them, do drop me an email.

Postscript In January 2021 I gave my four reels of tape to Kees Brinkerink, a pirate radio enthusiast and expert based in the Netherlands, who has produced his own transcriptions of them. In return, he has given me a number of other recordings of Big L (not on this website), and also provided the analysis of John Peel's Perfumed Garden programme.

|